Music, in its essence, is a reflection of time, culture, and human innovation. Over millennia, humans have created a stunning variety of musical instruments, each with its own unique sound and story. Yet, as new instruments emerged and musical trends evolved, many traditional instruments were left behind, their sounds fading into obscurity. Today, a global resurgence of interest in these forgotten instruments is breathing life into melodies that have not been heard for centuries, reconnecting us with the rich heritage of our ancestors.

India, with its vast cultural history, has been home to numerous musical instruments, many of which have become rare or near-extinct. Instruments like the rudra veena, ektara, and mridangam have historical significance, representing the spiritual and artistic traditions of ancient India. The rudra veena, for instance, was once a revered instrument in classical Indian music, often associated with the worship of Lord Shiva. Its deep, resonant tones created an atmosphere of introspection and spirituality. However, as the sitar and other more versatile instruments gained prominence, the rudra veena gradually faded from the mainstream.

Globally, similar stories abound. The lithophone, an ancient stone instrument from Vietnam, was used in ceremonial practices and is believed to be one of the earliest examples of musical craftsmanship. In Africa, the ngoma drums, central to tribal rituals, were often silenced during colonization, as traditional practices were suppressed. Europe saw the decline of the hurdy-gurdy, a medieval stringed instrument with a mechanical wheel that produced hauntingly beautiful drone notes. In South America, the charango, a lute-like instrument originally crafted from armadillo shells, struggled to survive colonization but is now making a comeback thanks to folk revivalists.

One of the reasons many instruments were forgotten is the shift in musical styles and audience preferences. As orchestras, bands, and electronic music emerged, instruments that required specialized craftsmanship or were tied to specific cultural contexts found less use. Additionally, colonialism and globalization played a significant role in erasing local traditions, as colonizers imposed their own cultural norms on the regions they ruled. Instruments deeply tied to indigenous or spiritual practices often faced suppression, leaving their legacy in the hands of a few dedicated custodians.

In India, the rise of Bollywood music overshadowed traditional folk sounds, contributing to the decline of regional instruments like the pungi (used by snake charmers) and the saraswati veena (named after the goddess of knowledge). Similarly, instruments tied to marginalized communities, such as the tumbak from Kashmir, became less visible as urbanization diluted local cultures. These instruments carried not just sound but the stories, rituals, and histories of the communities that created them.

Today, however, efforts are being made to revive these lost sounds. Across the globe, musicians, historians, and ethnomusicologists are working to rediscover, restore, and reintroduce forgotten instruments. In India, organizations like the Sangeet Natak Akademi are cataloging and preserving traditional instruments, while modern artists are incorporating these instruments into contemporary genres to keep their sounds alive. For instance, the ektara, a single-string instrument used in Baul music, has found its way into indie and fusion compositions, bridging the gap between ancient traditions and modern audiences.

Similarly, global efforts to revive forgotten instruments are yielding inspiring results. In Scotland, musicians are bringing back the clàrsach, a small Celtic harp that was a central part of Gaelic culture. In Japan, the biwa, a pear-shaped lute associated with storytelling, is being reintroduced in contemporary settings. Meanwhile, South American artists are crafting charangos using sustainable materials to respect modern ethical concerns while honoring tradition.

Technology has also played a crucial role in these revival efforts. Digital archives and 3D printing have enabled the recreation of instruments that no longer exist physically. For example, researchers have used historical texts and archaeological findings to reconstruct the aulos, an ancient Greek wind instrument. Virtual platforms and social media have made these rediscovered sounds accessible to global audiences, sparking renewed interest among younger generations.

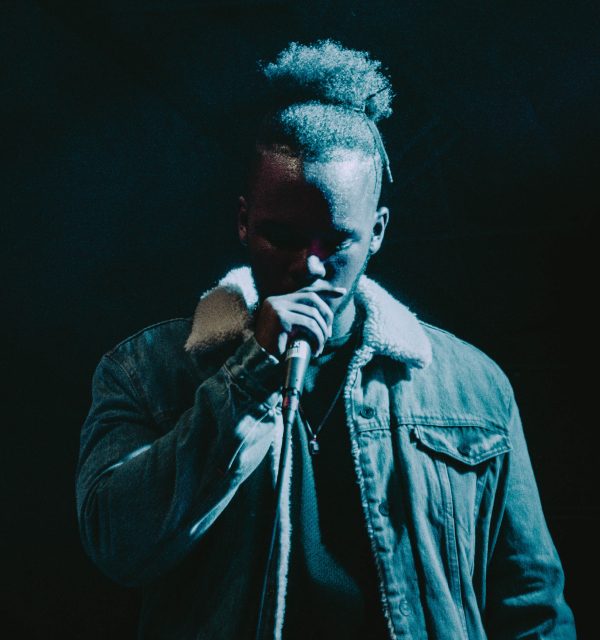

One particularly inspiring aspect of this revival is the blending of old and new. Musicians are experimenting with forgotten instruments in genres like electronic music, hip-hop, and jazz, creating fresh and innovative sounds. In India, artists like TM Krishna and Bickram Ghosh have incorporated traditional instruments into contemporary compositions, bringing their timeless tones to new audiences. Globally, collaborations between folk musicians and mainstream artists have introduced instruments like the hurdy-gurdy and the African mbira to listeners who might never have encountered them otherwise.

Reviving forgotten instruments is about more than nostalgia; it is an act of cultural preservation and renewal. These instruments hold the power to connect us to our roots, reminding us of the diverse sounds that shaped human civilization. They challenge us to listen more closely, not just to the music of the past but also to the stories and emotions embedded within them.

As we continue to rediscover these lost sounds, we are reminded of the immense creativity of our ancestors and the resilience of cultural traditions. In bringing these instruments back into the spotlight, we are not merely preserving history but creating a richer, more inclusive musical future—one where every sound, no matter how ancient, has a voice.